Opium—often called “poppy tears”—is the dried latex extracted from the unripe seed capsules of the Papaver somniferum plant, also known as the opium poppy. This thick, sticky sap is harvested through a traditional process where workers delicately score the surface of the green seed pods, allowing the milky substance to seep out. Once exposed to air, it hardens into a resinous yellowish-brown crust, which is then scraped off and collected.

Chemically, opium is a cocktail of powerful alkaloids. Around 12% of it is composed of morphine—an extremely potent painkiller that serves as the primary building block for heroin and other opioid drugs, both legal and illicit. Alongside morphine, it contains other natural opiates such as codeine and thebaine, as well as alkaloids like noscapine and papaverine, which have non-analgesic properties.

Interestingly, the term “meconium” originally referred to weaker, opium-like extracts made from other poppy species or different parts of the plant. Though that term now denotes the first feces of a newborn, its linguistic roots still echo the long-standing entanglement of humans and poppies.

The First Footsteps of Opium

The history of opium can be traced as far back as 3,400 B.C., when ancient Sumerians began cultivating the poppy in what is now Southern Iraq. They called it Hul Gil, translating poetically to "the joy plant"—an early nod to its euphoric effects. This botanical knowledge flowed from the Sumerians to the Assyrians, then on to the Egyptians, and eventually spread across the ancient world.

As trade routes like the Silk Road opened up, so did the geographic reach of opium cultivation. From the Mediterranean basin, its seeds were sown across Asia and into China, where it would eventually spark monumental geopolitical conflict in the form of the infamous Opium Wars during the 19th century.

Fast-forwarding to modern times, the consequences of our relationship with opium and its derivatives are staggering. Pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson was recently ordered by a court to pay a staggering $572 million in damages for its role in fueling opioid addiction—a case that signals a legal precedent similar to those once used against tobacco corporations.

Globally, it is estimated that around 16 million people have struggled with opiate addiction. These compounds—particularly morphine and heroin—are direct products of the poppy, a plant both revered and reviled. It is no coincidence that the opium poppy appears on the Royal College of Emergency Medicine’s emblem; its medicinal potency is undeniable. Yet the very substance that heals can also destroy, tying modern legal debates and pharmaceutical ethics to a plant humans have cultivated for millennia.

Poppy Myths, Medicine, and Mind-Altering Magic

Opium starts with the latex of the poppy plant—a thick, sappy secretion that can be consumed raw, dried, or processed. Though we can't be certain when humans first tapped into the poppy's mind-altering potential, archaeological evidence suggests its use stretches back to the Stone Age. Our ancestors likely discovered its properties by accident—perhaps by ingesting parts of the plant or simply licking the sap off their hands. What followed was a mythologization of the poppy across ancient cultures.

To the Egyptians, the poppy held sacred power. In Greek mythology, it was gifted by the goddess Demeter and linked to Hypnos (sleep) and Morpheus (dreams)—the latter being the etymological root for “morphine.” These associations weren't merely poetic. The calming, sedative effects of opium were so profound that the poppy was often regarded as a divine gift.

It’s important here to distinguish terminology: opiates are directly derived from opium, while opioids are synthetic or semi-synthetic versions created in laboratories. Both types affect the body in similar ways by targeting opioid receptors in the brain and nervous system.

There are four main classes of opioid receptors: mu, kappa, delta, and nociceptin. When opiates bind to these receptors, they reduce neurotransmitter activity and dull pain signals—a process known as analgesia. However, this same mechanism also alters brain chemistry, leading to dependency, mood shifts, and, eventually, addiction. The ancient promise of relief comes with a modern warning label.

Even in early medical practices, opium was a double-edged sword. The renowned Persian physician al-Razi, who lived from 854 to 925 A.D., used it as one of the earliest anesthetics. Meanwhile, the Mughal emperor Jahangir was so deeply addicted that his wife was left to govern in his stead. Turkish society, too, was said to be enthralled by the poppy, with the common saying that no man would hesitate to spend his last coin on opium.

Laudanum and the Birth of Medical Addiction

One of the most widespread and historically significant derivatives of opium was laudanum—a liquid tincture of opium typically mixed with alcohol. It was first standardized by the English physician Thomas Sydenham in the 17th century. His 1676 formulation was lauded as a universal remedy, effective against ailments ranging from chronic pain to persistent coughs.

Despite its addictive nature, laudanum quickly gained popularity across Europe. Compared to other "remedies" of the time—which often included toxic metals like mercury—it was seen as relatively safe. Plus, its constipating side effects were even welcomed in an era plagued by poor sanitation and frequent diarrhea.

It’s no surprise that many historical figures became dependent on it. In 1821, essayist Thomas De Quincey penned Confessions of an Opium Eater, a hauntingly vivid memoir of his spiraling addiction, offering readers a firsthand glimpse into both the ecstasy and agony of life under opium’s influence.

China, Empire, and the War for the Poppy

While many nations fell under the poppy’s spell, few experienced its impact as acutely as China. As opium addiction spread, the Chinese government sought to restrict its importation. However, British traders—eager to keep selling the poppy products cultivated in colonial India—resisted these efforts with military force.

Thus began the Opium Wars, a pair of bloody conflicts between China and Britain (with France joining the latter in the second war). The First Opium War raged from 1839 to 1842; the Second from 1856 to 1860. The British emerged victorious, forcing China into unfavorable trade agreements that decimated its economy and led to the ceding of Hong Kong.

Around this time, a British chemist named Charles Romley Alder Wright attempted to engineer a non-addictive form of morphine by boiling it with various acids. Ironically, he ended up creating diamorphine—better known as heroin. While initially marketed by Bayer Pharmaceuticals as a cough suppressant, heroin was soon pulled from shelves once its addictive nature became obvious. Codeine and other opiate derivatives began to take its place in the pharmaceutical world.

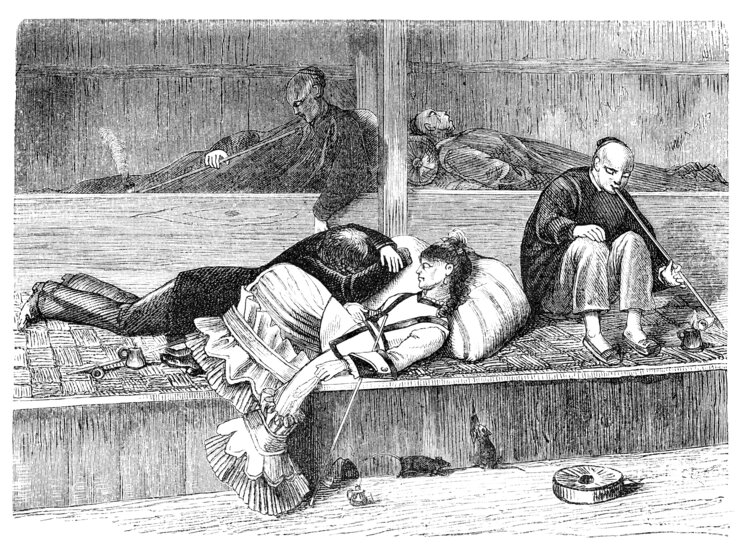

Opium Dens, Immigration, and Prohibition in the West

As Chinese immigrants settled in the United States during the 19th century, they brought with them the tradition of opium dens—dimly lit spaces where users could smoke the drug and achieve fast-acting, intense highs. These establishments ignited moral panic and xenophobic sentiment, eventually fueling anti-immigration laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

This era also marked the beginning of drug regulation in the U.S. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 mandated that all addictive substances be labeled on packaging. Just three years later, the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act outright banned the importation of opiates for recreational use, though enforcement often carried racial undertones.

Pathologist Hamilton Wright called opium "the most pernicious drug known to humanity,” leading to the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, which heavily taxed and restricted access. In the UK, the Rolleston Committee Act of 1927 allowed doctors to prescribe opiates to addicts, treating addiction as a medical issue rather than a criminal one—a policy that would eventually be reversed.

Modern Policy, Portugal’s Bold Move, and the Chronic Pain Dilemma

In 1961, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs united nations under a global treaty to control opium and other narcotics. This led to the UK’s 1964 Drugs (Prevention of Misuse) Act, which began treating possession as a criminal offense. The 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act later categorized substances into Classes A, B, and C—a framework still in place today.

Yet the criminalization of addiction remains hotly debated. Portugal, for instance, once had one of the highest heroin addiction rates in Europe. In response, the country decriminalized possession in 2001, redirecting addicts toward treatment rather than prison. Since then, Portugal has seen a marked decrease in overdose deaths, HIV infections, and drug-related crime—a model that challenges the punitive approach taken elsewhere.

In recent years, attention has returned to legal opioids, especially in the treatment of chronic pain. Though opiates are unmatched in managing acute or end-of-life discomfort, studies show little benefit in long-term use. Despite this, prescriptions have surged—fueled in part by aggressive pharmaceutical marketing.

In the 2019 Oklahoma case, Judge Thad Balkman found Johnson & Johnson guilty of:

"promotion of the concept that chronic pain was under-treated (creating a problem) and increased opioid prescribing was the solution."

Doctors, often strapped for time and faced with complex patient needs, may default to opioids as an expedient remedy. This troubling cycle underscores the ongoing dilemma: how do we balance the poppy’s healing promise with its destructive power?

From sacred offering to courtroom controversy, opium continues to shape medicine, law, and lives—and the conversation is far from over.